The mid-nineteenth-century United States was notable for its rapid expansion, especially in the areas of geography, population, and economy. Yet despite a common language, religious faith, and history, two distinct economic and cultural regions (North and South) were coming to see each other as threatening to their own ways of life and visions of the American republic.

Economically the American South relied almost entirely on crops grown by slave labor, particularly cotton. Although most Southerners did not own slaves personally, this dependence on slavery had a profound impact on Southern culture, making white Southerners extremely defensive about their "peculiar institution. " Their sensitivity was heightened by fear of slave insurrection, for slavery was as much a system of race control as of labor. Thus Southerners reacted sharply to any possible threats to slavery. They defended themselves from attacks on the slave system and masked internal dissension by emphasizing the purity of what they saw as a chivalrous society. Southerners came to perceive the North as a region dominated by avaricious, exploitative industrialists whose values were subverting the virtuous agricultural republic envisioned by America's founding generation.

Most Northerners did not favor interfering with slavery in the Southern states. Whatever moral aversion to the concept of slavery many of them may have felt was less important than maintaining a harmonious union of states. Yet, rocked by massive social change arising from burgeoning industrialization, increasing materialism, and large-scale immigration, Northerners veiled doubts about their society by focusing on their industriousness and self-reliance and praising free-labor ideals by which any man could earn economic and social respectability. They saw the South as the antithesis of that ideal, a place where slaveholding degraded the status of labor and aristocratic planters dominated society and government, in short, a society opposed to the ideals of the republic's founders.

Southerners, anxious to protect the viability of slavery, worked to promote their institution's spread into the western territories. Northerners, however, saw the territories as the basis of an "Empire of Liberty," where equal opportunity and free-labor values would reign, and they feared having western emigrants exposed to the competition of slave labor. These opposing perspectives led both sides to interpret each other's actions as aggressive and threatening. The more Southerners fought to keep the territories open to slavery, the more Northerners embraced the idea of a mighty oligarchy of slave owners—the " slave power"—conspiring to control the federal government and open all America to slavery. In the mid-1850s many Northerners joined the new Republican Party, with the exclusion of slavery from all federal territories as its primary goal. Southerners viewed this party as a blatant attempt by Northern antislavery forces to control the national government and attack slavery.

When Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860 without a single Southern vote, the seven states of the Deep South decided that the federal Union could no longer protect slavery. They seceded and formed their own government, the Confederate States of America. When armed conflict erupted over federal occupation of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, Lincoln called for volunteers to maintain the Union by force. Four more slave states seceded, afraid to remain in a Union held together by armed coercion. The war began.

Both sides drew on a powerful devotion to the legacy of the Revolution. Southerners associated themselves with the American colonists' defense of their homeland from a distant, power-hungry invader and fought for a purified version of the republic they believed Northern values had corrupted. Northerners struggled to save the Union of the founders—the grand experiment in republican government—from those who would corrupt and destroy it.

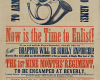

Hundreds of thousands of Northerners and Southerners sprang to volunteer, as parades and banquets across the country stirred patriotic fervor and pressured young men to enlist. Almost everyone expected a short war—one brief campaign or even a single, all-out battle. Volunteers soon found that their visions of glory did not match the reality of life in camp, where they spent most of their time. They drilled for a part of every day and spent the remainder fighting profound boredom by reading, writing letters, playing pranks, performing plays and concerts, and other activities. Religion was popular among many soldiers, and camp revivals were common. But perhaps the most significant factor in camp life was disease, which killed far more men than battle did.

Since volunteer regiments were drawn from single towns or regions, home community life carried over into the armies. That carryover was crucial to the courage displayed by soldiers in the terror and confusion of battle: for many, what kept them in the lines was knowing that their families and communities would find out should they run. Loyalty to one's companions, what sociologists call "small-group cohesion," was another important factor in the steadfastness-under-fire displayed by most Civil War soldiers. Such courage prevailed despite staggering carnage: it was common for a unit to suffer twenty-five to fifty percent casualty rates in battle. In all, disease and battle killed over 620 thousand men in the Civil War.

With America's capital and industry concentrated in the Northern states, the Confederacy faced tremendous challenges in running a war. The government tried numerous means of financing the war, including borrowing and taxation. A ten percent "tax in kind," payable in agricultural products owing to the region's money scarcity, was particularly odious to Southerners because of the harsh measures employed by government collectors. Yet these sources proved inadequate, and the Confederate war effort was funded primarily by the printing of over a billion dollars of unsupported paper money. Inflation stemming from this policy and from widespread shortages shattered the economy, resulting in massive deprivation and food riots.

The dearth of Southern industries forced the government to direct war production itself, building foundries, shipyards, and other necessary works, and, by the end of the war, seizing all railroads and telegraph lines and strictly regulating all imports and exports. A bureaucracy over seventy thousand strong controlled this far-reaching apparatus.

In the spring of 1862 the Confederacy instituted America's first centrally directed draft. Conscription sparked a great deal of resistance, but the most bitterly resented aspect of it was what was called "the twenty-nigger law, " which exempted one white man on every plantation with twenty or more slaves. Small farmers felt that they were unfairly bearing the brunt of the war's hardships.

Inflation, shortages, the tax-in-kind, conscription, and the "impressment " of produce and livestock by Confederate armies all produced resentment and dissension. Women were hit especially hard by the demands of war, frequently left alone to perform work for which they were ill-prepared. Many upper-class women felt betrayed by a society that had led them to expect to be cared for and protected, while lower-class women struggled to keep their families and farms intact. As the war progressed many wrote desperate letters begging their men to come home. These letters were no doubt a primary cause for high Confederate desertion rates late in the war.

Despite such intense war weariness, most white Southerners remained devoted to the cause. Through four brutal years of war white men continued to fight and white women continued to run farms and plantations. In fact, mounting casualty lists added to their determination, forcing them to find some meaning behind the destruction and increasing their hatred of Yankee armies. Not until April 1865, when the surrender of Robert E. Lee's seemingly invincible Army of Northern Virginia broke the spirit of the Confederacy, did the underlying will to fight cease.

Although the nation's rate of economic growth slowed during the war, largely owing to the expense of maintaining a military totaling 2.2 million men, virtually every aspect of the Northern economy flourished. Directing this boom were activist Republican policies. The Republican Congress instituted such dramatic reforms as a national banking system, income and excise taxes, and the granting of millions of acres of public lands for the support of railroads, colleges, and western emigrants. Although their aim was to fuel the economy and advance the public good, the unforeseen consequences of these policies were the concentration of economic power in the hands of northeastern bankers, the strengthening of industrialists at the expense of laborers, and the laying of a general groundwork for the massive economic consolidation of the Gilded Age.

Although farmers, the majority of the Northern population, flourished during the war, not all segments of the population thrived. Wartime inflation outran industrial wages, provoking labor unrest. The Lincoln administration's use of federal troops against strikers and its restriction of critics' civil liberties aroused opposition among workers. When, in the spring of 1863, the government announced a new conscription policy that allowed exemptions for those who could provide a substitute or pay a three-hundred-dollar commutation fee, resistance broke out in cities across the North. For four days in July, the worst riot in U.S. history raged in New York, killing over one hundred people. Much of the violence there consisted of Irish laborers' attacking free blacks, blaming them, in the wake of the government's new emancipation policy, for the war.

Most Northerners went to war not to attack slavery but to preserve the Union, which had come to symbolize individual liberty, self-government, and law and order. But as the contest wore on more and more Northerners became convinced that victory would require striking at the heart of Southern society, abolishing slavery and remodeling the South in the Northern image.

The institution of slavery began to disintegrate as soon as Southern men left farms and plantations for the army, leaving behind them a strange new society composed of white women and slaves. From the beginning the slaves viewed the conflict as a divinely directed war for their deliverance, and they acted on this idea by escaping by the thousands to Union encampments whenever Northern armies came near. In addition to undermining the slave system, these refugees forced the Northern people to consider the moral aspects of slavery and convinced increasing numbers of Northerners that the slaves should be freed.

Lincoln himself came to this conclusion by the summer of 1862. Following the Union victory at Antietam in September, he announced his intention, as commander-in-chief, to abolish slavery and to utilize African Americans as soldiers. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Civil War became a war to end slavery as well as to save the Union. Many Northerners opposed this radical move, but the dragging on of the war convinced more and more people of the need for it. Moreover, the distinguished service of almost 180 thousand black troops—most of them former slaves, and all facing segregation, inferior pay, and other forms of discrimination—convinced many whites of the utility of arming African Americans and created a climate of sympathy for blacks, which had a great influence on the course of postwar Reconstruction.

The Civil War was a watershed event in American history. It resolved constitutional ambiguities concerning federal supremacy and the legal right of secession, and, by the end of the nineteenth century, resulted in a truly unified nation. Perhaps more important, it freed over three million slaves and wrote into the Constitution full citizenship rights for African Americans.

White Southerners did not adapt easily to the new racial order. As soon as possible they turned to blatant racist appeals and terrorist campaigns to reverse black political and social advances. By the 1890s the Jim Crow system was replacing the institutionalized race control lost with slavery. This system would dictate race relations into the 1960s. In the meantime the economic and social devastation of the South was terrific, and the region would remain an economic backwater for decades.

In the North the wartime economy initiated the massive economic consolidation that occurred during the last decades of the nineteenth century, setting the stage for the modern American economy. Moreover, by bringing to fruition the most radical of the antebellum reform movements—abolitionism—and by subjecting a generation of young men to military discipline, the war marked the climax of the idealistic reform impulse. Thenceforth, a more conservative intellectual climate prevailed, which emphasized organization and professionalism.

The Southern myth of the Lost Cause arose quickly, positing that the North won not because of superior skill or courage but through sheer force of numbers and industrial might, thus bringing no dishonor to Southerners, who had been doomed to fail despite the most valiant resistance. This myth recalled for Southerners the Old South for which they had fought as a land of idyllic plantations and contented slaves. These images have been propagated by such influential films as Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone with the Wind (1939) and are popular today among legions of Civil War buffs and reenactors.

Meanwhile the North created its own romanticized mythology, portraying the war as a moral crusade to erase the stain of slavery. It found its hero in Abraham Lincoln, whose image as a humble, honest frontier rail-splitter who rose to the highest office, stood up to the aristocratic slave power, and became the "Great Emancipator" captured perfectly the image of war Northerners wished to cherish. This image of the war has been maintained through Carl Sandburg's monumental popular biography of Lincoln (1926; 1939) as well as later novels such as The Killer Angels (Michael Shaara, 1974) and films such as Gettysburg (1993).

War and the Representation of War

CivilWar@Smithsonian (Smithsonian)

American Centuries: Highlights: Military

African-American Odyssey: The Civil War (Library of Congress)

Historic American Sheet Music: United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Songs and Music

Making of America (U Michigan)

The Charters of Freedom: Impact of the Charters

Wright American Fiction: 1851-1875

Rebellion: John Horse and the Black Seminoles, The First Black Rebels to Beat American Slavery

America Singing: Nineteenth-Century Song Sheets (Library of Congress American Memory)

African-American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship (Library of Congress)

The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: Military Activities and U.S. Civil War

Antislavery Literature: Legacies

African-American Sheet Music, 1850-1920: United States

With Malice toward None: The Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Exhibition (Library of Congress)

Revising Himself: Walt Whitman and Leaves of Grass (Library of Congress)

The African-American Experience in Ohio, 1850-1920 (Library of Congress American Memory)

The African-American Pamphlet Collection: Civil War (Library of Congress American Memory)

Documented Rights: Let My People Go (National Archives)

The African-American Mosaic: Abolition (Library of Congress)

Encyclopedia of American Studies, ed. Simon J. Bronner (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), s.v. "Civil War" (by Russell McClintock), http://eas-ref.press.jhu.edu/view?aid=581 (accessed November 21, 2012).